Does new opera succeed by parceling history for a post-pandemic world? While Terence Blanchard’s Champion premiered at the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis in 2013, it has made an impactful impression in its Metropolitan Opera appearance this 2022-2023 season. A historical opera, it recounts the life of Emile Griffith, a welterweight boxer who dominated his sport in the 1950s-1960s, with melodic jazz and snappy dance numbers—a sort of Hamilton for the highbrow art form. In its last performance on May 13, I listened to the opera as much as looked to the audience, wondering if I was seeing the future of opera or a hopeful glimpse of what it could be.

The opera is split between present and past, with Ryan Speedo Green starring as the “young” Griffith and Eric Owens playing the elder. Owens begins the opera, bent and confused, suffering from dementia. Soon memory whisks him from his present-day haunting to his joyous youth in St. Thomas with lively singing and dancing numbers replete with bright brass and drums. But the dazzle is pierced by a fight announcer at the side of the stage, as though an unshakable voice in Griffith’s own mind and a continuous reminder of the trauma he experienced: “Only shadows in the night” as one aria goes.

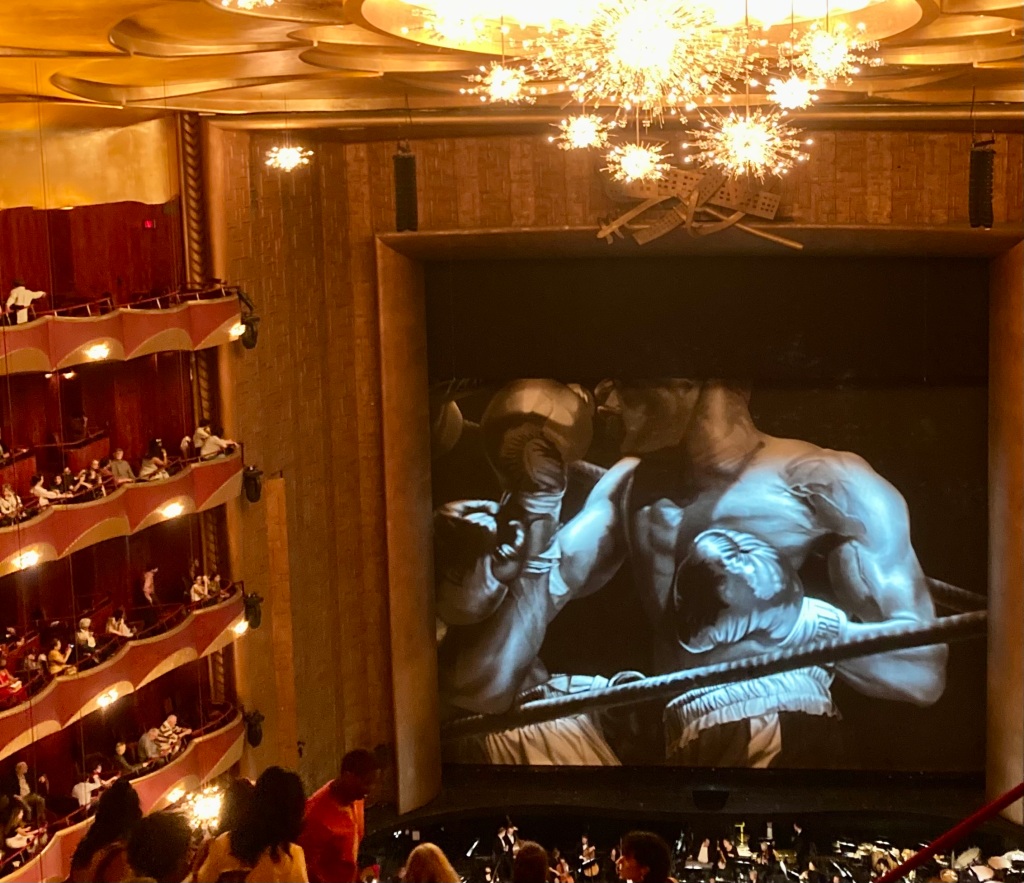

The recurring announcer, appearing simultaneously on the corner of the stage and Griffith’s memory, foreshadows the centerpiece and climax of the story, a critical match at the height of Griffith’s career. In the match, he kills Benny “Kid” Paret after Paret hurled a homophobic slur at him, “maricón”—a Spanish word that the libretto and score work together to punctuate tauntingly. The scene itself is masterfully choreographed and lit, cinematic, in fact, and brutal to behold. The program notes that Griffith delivered “seventeen blows in less than seven seconds.”

One way to understand Champion is as an exploration of how memory works with and around trauma. Whenever the elder Griffith appears, he is crouched, physically weighed down by a tormented past: he carries a burden even when he can’t recall why he feels burdened. In addition to dividing past from present, the story also splits to capture both sides of Griffith’s double life as a gay man. Mirthful scenes in one of Manhattan’s gay bars fade to his courtship and quick marriage to Sadie (sung with glitz by soprano Brittany Renee) in the second act.

The opera is built to offer a version of reconciliation, and given our current state of affairs, this is perhaps why audiences are so drawn to its story right now. The fight and its aftermath focus on Griffith’s crisis of identity and discrimination as much as on the shock of having killed a man. Phrases like “what makes a man a man” set to melodic, hum-able songs with driving bass lines and catchy percussion revolve visually around series of squares that light up blue, red, and orange, frame within a frame, that steadily power onward. It’s an opera that holds the audience’s hand to process a devastation that is both real and recognizable.

Historical operas, works that represent and recreate history, perhaps give a foothold for new audiences, telling a story in an unfamiliar way about a known entity. I’m thinking of Adams’ Nixon in China, Glass’ Satyagraha, but also operas like Handel’s Giulio Cesare—it’s not an original idea to make an opera about a historical figure, but it does seem to be trending in recent years.

History is selling. In this opera, it’s bringing to light pain that we’ve forgotten or systemically hidden, and people are showing up for it. Notably, Champion is only the second opera the Met has staged by a Black composer, the story it tells but one erasure of many that we’re slowly unearthing.

Never heard of this before. Now I want to see the opera and know more about the history.

LikeLike