“I am jealous of everything whose beauty does not die,” Dorian Gray laments upon just having seen his portrait. In it, he realizes something worse than mortality—that one day he will grow old and “become dreadful, hideous, and uncouth.” That youth is fleeting and that to be beautiful is worth everything.

In a new production at Santa Fe Opera, director Stephen Barlow has reimagined Mozart’s 1787 opera Don Giovanni as Oscar Wilde’s Victorian gothic novel A Picture of Dorian Gray. Known for his smart use of color and clever aesthetic, Barlow doesn’t disappoint here, but as far as philosophical parallels go, I would wager Barlow watched the movie and didn’t read the book.

In the program notes, Barlow says that he was inspired by a modern film adaptation in which Dorian is holding a briefcase that has the initials DG on it embossed in gold. Yes, their initials are the same, but what else? Rooted in love, loyalty, betrayal, revenge, and sweet justice, Don Giovanni rightfully holds the title as the perfect opera in most circles. The pacing is right, the music is stunning, the plot is timeless. It also doesn’t hold punches. The story begins with Don Giovanni sexually assaulting Donna Anna and then killing her father when he comes to defend her; the story ends with Giovanni burning in hell for his many misdeeds. Morality, above all else, triumphs.

I’ve always understood it as a rare story of feminism in the midst of so many operatic female characters who wilt away and die. If Don Giovanni becomes Dorian Gray, he assumes a backstory of a mad pursuit for youth and beauty at all cost. How does Giovanni’s decree that “Freedom is our only rule” translate to Dorian’s threat, “When I find that I am growing old, I shall kill myself”?

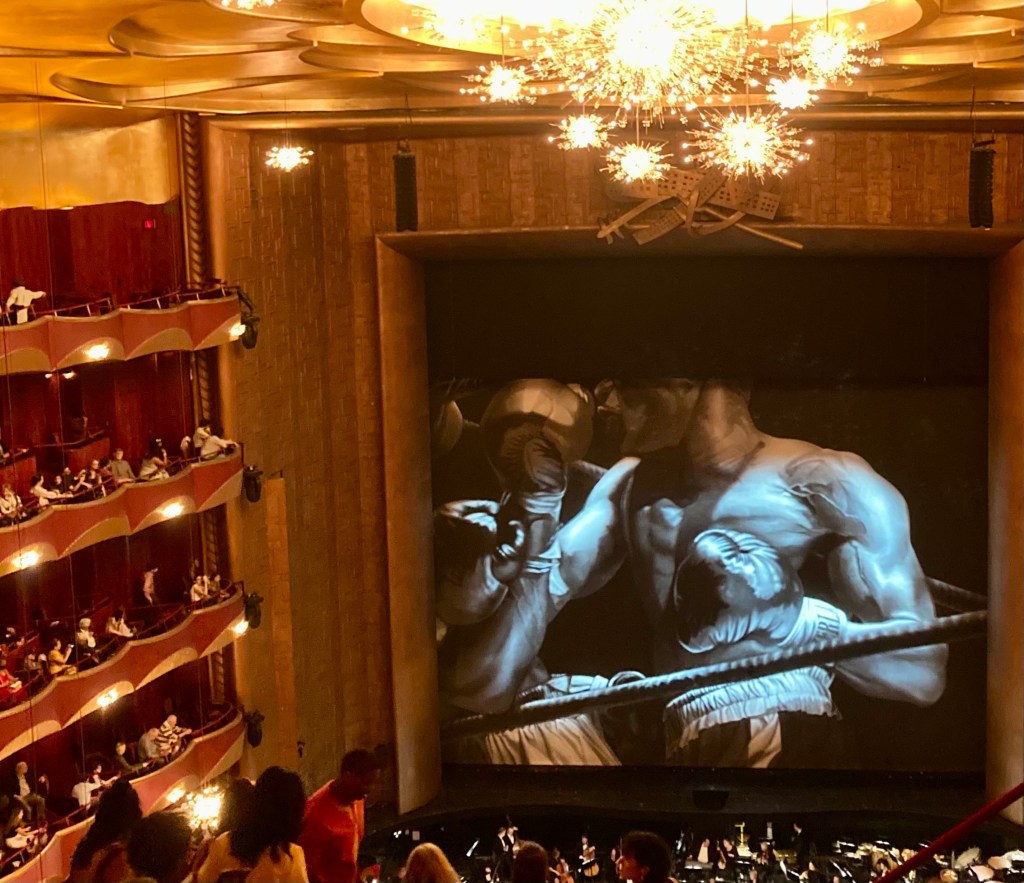

Missing dramaturg homework aside, beauty reigns in this production and in its singing. In the title role, Ryan Speedo Green continues to thrill and develop. I last heard him at the Met as Emile Griffith in Terence Blanchard’s 2013 Champion, a very different opera, and he’s proving to be a singer with range who will stun across styles. The set is creative and cunning in its use of space, with walls sliding to reveal lampposts and ornate wrought-iron fences, sumptuous Victorian hotel lobbies, and Don Giovanni’s portrait-laden den (let’s forget that Dorian Gray hides his portrait for most of the novel) replete with a crackling fireplace. Bright pops of orange and red arise in key plot moments against mostly dark greys and blues. Rachael Wilson, as Donna Elvira, wins the acting prize, and Rachel Fitzgerald, who stepped in at the last minute to replace Teresa Perrotta as Donna Anna, certainly earned her spot on stage in a svelte performance.

As an open-air theatre nestled in the New Mexico mountains, Santa Fe Opera brings an aesthetic clout unlike any other. Last night, the opera began in the midst of a storm that persisted throughout. Lightening snapped across the sky. Rain drummed around the edges of the stage. As justice ultimately found Don Giovanni, the ethics of it all took a larger frame. Youth may be fleeting, but nature is ever ascendant.